This article is the third entry in a series on individual poems. Read the rest of the reviews, essays, or poem-talks here.

“Passing in the Hallway” by Raoul Fernandes

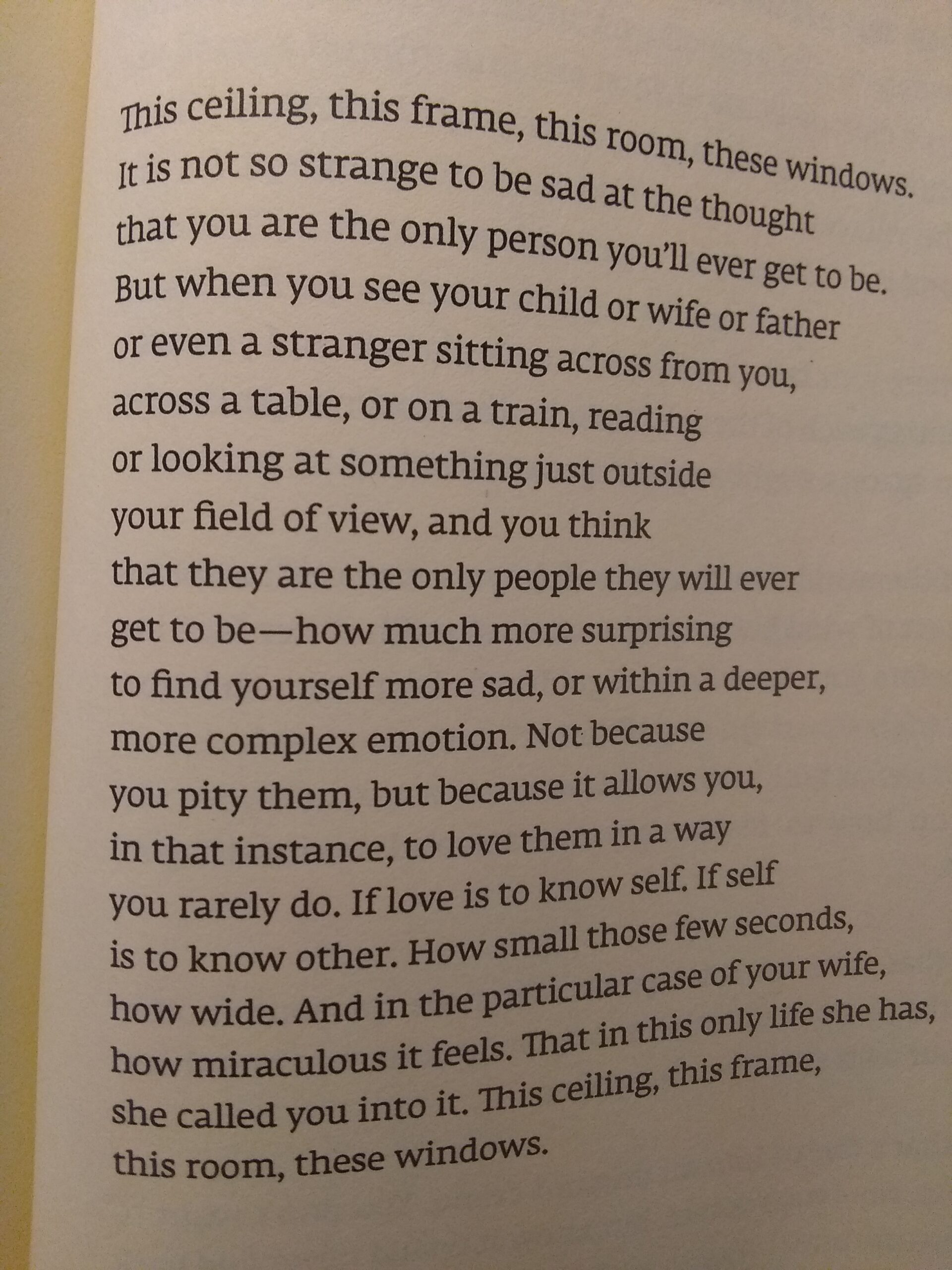

The poem “Passing in the Hallway,” written by Raoul Fernandes, is included in Transmitter and Receiver (Nightwood Editions, 2015). I’ve included a photo of the poem below.

“Passing in the Hallway” begins with a sentence fragment: “This ceiling, this frame, this room, these windows.” Four adjectives and four nouns, paced equally with commas. At first read, I seek the nouns for substance — for qualities that might orient or ease me into the poem: as if wading into murky waters, unsure of my footing. But the nouns are defiantly vague: “ceiling … frame … room … windows.” The barest of architectural indicators, mostly square or rectangular, but otherwise featureless. Not helpful.

It’s the adjectives here — “this” and “these” — that are most significant. From “this” and “these,” we can glean that the structural frames spoken of are at-hand, immediate (so, not “that,” not “those”). This quality nudges me back to the nouns and helps me see them differently. When I say, ceiling, what do you see? When I say, room, what appears? Something appears. So let’s assume that what appears to you is this ceiling; what appears in your mind are these windows — not something else, or elsewhere, but simply whatever appears.

Okay. Is this a home? Is it the mall? Is it your barren corporate office, a Burger King or a synagogue? Where are you right now, or where are you transported to? Let’s imagine that this is the place in which we are “passing in the hallway” — you, me, the speaker, the author — at least to begin.

What follows is a change in syntax track, from fragment to complete sentence, and a non-sequitur from our at-hand architectural sign-posts: “It is not so strange to be sad at the thought/ that you are the only person you’ll ever get to be.” It’s not conversational (“It is not so strange” is a written convention, almost never spoken). But the first line has two pleasing dactyls (“to be sad at the thought”), helping us swim past the slow pace of the previous line and into deeper water.

The third line delivers the poem’s first point of meditation in direct, chatty diction: “you are the only person you’ll ever get to be.” The second-person address helps (as I speak about in my post on “Jack Pine”) pull the poem out of the private, or personal, and into a discussion of life more generally. And yes, such a scenario, presented as such, could be sad for most of us. It’s the kind of sadness many children experience as they realize that life is limited, and slowly gets more limited. Options diminish as we age; the field of possibility recedes until our choices necessarily close doors. We are also confronted, as children, with the other injustices of being and time: our birth, our sex, our parents and class, our language and geography, all presented to us without our consent.

(And yet — and let’s earmark this for the end — the poem isn’t positing a metaphysical certainty; it’s “the thought” that one might only ever “get to be” one single person that is “sad.” It’s not the actual being that one person, but the specific consideration of such a situation of limited potential. So, the speaker is not saying that being is sad. Thinking about it is.)

The speaker marks the pedestrian, everydayness of this kind of sadness (more of a wistful longing, maybe, than a depression) with the next line, composing a relatively long sentence, all starting with “But.” Here’s the first half:

But when you see your child or wife or father

or even a stranger sitting across from you,

across a table, or on a train, reading

or looking at something just outside

your field of view …

As this poem picks up, I start to feel the accumulation of all these non-specific, generalized nouns. We just encountered “this ceiling, this frame, this room, these windows.” Now we’re directed to envision “your child or wife or father/ or even a stranger.” It’s your “child or wife or father,” so that’s easy, since in this case each person belongs to you and should be easily summoned to mind; and with the indefinite article attached to the “stranger,” the speaker is letting you loose once again: imagine whoever arises naturally. This indefinite stranger sits at an indefinite “table,” or, if that doesn’t serve you, “on a train,” but not a particular table or train. They might be “reading” [something] or they might be “looking at something” (but not something in particular). Besides, it’s “just outside/ your field of view,” so you wouldn’t know anyway. Adding to the vagueness is a pile-up of prepositional phrases — “across from you,” “across a table,” “on a train,” etc. — extending this set-up with extra letters and giving a spatial arrangement to a scene that floats in an undefined fog.

If I were trying to teach poetry to students, I would probably advise against this; I would recommend grounding the poem in vivid imagery, cutting unnecessary clutter, enlivening verbs with sparkling energy. Not because vagueness never works — and “Passing in the Hallway” is an example of why it can work, as we’ll discuss — but because mostly it doesn’t, and it’s a hallmark of amateur writing, of not quite understanding your subject or muddling your way through a concept you haven’t quite pinned down.

Digression aside: with “across from you” rhyming snugly with “your field of view,” the sentence and the poem itself reaches a snapping point. Sensing this strain, the speaker abandons another list of undefined objects, pivots on the comma, and delivers the central (or deeper) meditation on YOLO, or having one life only:

… your field of view, and you think

that they are the only people they will ever

get to be — how much more surprising

to find yourself more sad, or within a deeper,

more complex emotion.

With such prosaic diction, we trust that line breaks and enjambment will provide gravitas, rhetorical punch. Ending the line with “and you think” carries with it a natural pause we might linger on, if we were speaking, knowing this is the true set-up of our take, our confession or rumination. I find a line like “that they are the only people they will ever” kind of bold: it has no music. But it does give us the phrase “get to be” as a standalone beginning, drawing our attention, giving it a sense of finality, like a verdict. The em dash feels like a pause in thought, wherein feeling or emotion flood — a feeling we are then told is “surprising”; the dash serves as this silent pause in an unfolding, sharp realization, a catch of breath before we’re able to give words to whatever we’re feeling.

We find ourselves “more sad, or within a deeper,/ more complex emotion.” Notable, I think, is the speaker’s choice of “more sad” over “sadder.” Both are correct, but “more sad” is clunkier, more childlike, a mark of a limited vocabulary. It keeps our terms vague, and thus consistent. And it feels like a deliberate attempt to denude the imposingness of this meditation, to pull back some of the emotion, as if the speaker has risked too much in the telling and now wishes to avoid appearing overzealous or grandiloquent (a kind of rhetorical shrug, an “ah shucks,” or tsk).

So what is the “deeper,/ more complex emotion”? On first read, my immediate impulse, given another vague definition, is to provide my own response. Imagining a person, a family member or stranger, to be in possession of one small and limited life inspires a pang of pity for their misfortune. I feel pretty sure about this response, even on a second look: yes, it’s pity, or sorrowful compassion, that I’m feeling. The poem has become more interesting now. We’ve taken one form of sadness we often feel privately and upped the ante: the sadness that you feel for your own diminished horizon is now expanded to cover and endow all people, in all times (and we can imagine now why the rhetorical ‘shrug’ was deployed — I’m trying to get between your ribs, the speaker is saying, not bludgeon you over the head with this brief glimmer of empathy).

But immediately we’re told that “pity” isn’t what we’re feeling at all: “[the thought] allows you,/ in that instance, to love them in a way/ you rarely do.” So it’s love I’m feeling! Well, that’s better than mere pity, isn’t it? I think the speaker has, through the various strategies deployed, earned their use of this loaded word, but we might quibble with the thinking. Was it mere pity we felt for these imaginary or not-so-imaginary people, each with their small windows? In other words, do we need another step to transform this pity into love, to make that alchemical transformation between a small shiv of sorrow for another and a true loving-kindness for them, a wish for them to be happy, free, without pain, and loved in turn, without any involvement of our own wish for the same? Is this likely the result of prolonged compassion for someone else, or is it love right from the jump? Either way, it inspires inquiry into our own emotional responses, and I admire that quality.

What comes next is the speaker’s justification for this leap from pity into L-O-V-E: “If love is to know self. If self/ is to know other.” And our speaker — full of vagueness — gets away with using the word ‘self,’ deserving of its own series of deep inquiries, with a kind of chatty, intimate charm. There’s a relative, conventional, untheoretical sense of ‘self’ implied here and the gist is simple: understanding that another person is much the same as you, with your own host of hopes and fears, is a way of humanizing them, seeing yourself in them, sharing their burdens, expanding your realm of compassion. To love, implies the speaker, we must feel as they feel, see as they see. Love implies an emotional understanding of how we are composed, how we feel and think; to love we must not be victims of our own emotions, cravings, illusions, etc., or we’ll be trapped in a small self. The relative, efficient way of summing this up would be the hackneyed idea of self-knowledge, or self-awareness. The speaker wisely backs away from deeper investigation; to push on, to try to name this revelation as ‘self-knowledge,’ might risk exposing the philosophical flimsiness of this as a manifesto.

For the speaker of “Passing in the Hallway,” we are now loving others in a way “we rarely do.” The shock of the self in the other, or the other as the self, drops our typical reactions to ‘other people,’ which are wary at best, openly hostile at worst. For the Christian, the Kingdom of Heaven is at-hand when we dissolve formal bonds of fraternity, parentage, allegiance, and so forth, and instead see every human being, every neighbour, as our own blood: our brothers and sisters. In arousing bodhicitta, the bodhisattva of Buddhism looks upon every sentient being as a mother-being, as close as a mother to her only child, and thus sees every creature with nurturing loving-kindness. This is a love that goes beyond words or gestures; it is not intellectual, theoretical. It must be felt or experienced.

This is also something to be practiced. Much to our “more sad” condition, we don’t see our ‘selves’ in strangers and become permanently affected, or converted — at least not most of us. From a Christian perspective, we are mostly not saints. From a Buddhist perspective, we carry tremendous karmic defilements, habit energies, that root us back into poisonous selfishness and literal ignorance of our kinship. “How small those few seconds,/ how wide,” says the speaker, with simplicity. The seconds we realize, as if through epiphany, that our self is the other are exceedingly short. But they are also potentially “wide,” which, to me, summons the idea of depth and breadth — that they are not only some of the most important “seconds” we could have the fortune of experiencing, but they might contain, or give access to, another dimensionality of life that contains a revolutionary feeling, meaning and happiness. All along, there was another life to live after all. Everything remains the same but is also radically transformed.

Now, we started with a dilated view, incorporating strangers on trains, across tables; it’s time to take this same sentiment, this understanding of true intimacy, and contract it to someone we already care about.

And in the particular case of your wife,

how miraculous it feels. That in this only life she has,

she called you into it.

As children, we might ache at the realization that we don’t literally get to be astronauts sailing over the moon, or hunters on some Neolithic plain, or ladies in voluminous gowns sipping tea in a Paris salon. But as we age, we might mourn all the other, smaller doors closing: we also don’t get to live in every city, or travel the world; we don’t get to adopt every sad dog we see, have 1,001 careers in 1,001 fields, earn every degree, write a symphony or cookbook or become a film star or champion boxer, or marry 500 lovers. Simply by living there are choices we are forced to make, and stick with, or face horrible anxiety and anguish. In the “particular case of your wife,” she has endured these and innumerable other small sufferings in “this only life she has.” That’s why it feels “miraculous” to have been “called … into it.” She chose you! With all the generality throughout this poem, it almost feels odd to see the speaker focus on “wife” and not, say, “your husband or wife,” but consistency would ruin the single-gendered ease of “That in this only life she has,/ she called you into it.” It’s better, even if less universal, to keep this to a single person, a single imaginary subject, who can serve as a stand-in for the reader’s wife, or wife-equivalent, or whatever, or even to arouse feeling for the speaker, who is, I think, clearly picturing a real-life wife (but I digress …).

And here we return to the first fragment: “This ceiling, this frame/ this room, these windows.” I said it was a non-sequitur to move from this fragment to the second line, which introduced how “It is not so strange to be sad at the thought/ that you are the only person you’ll ever get to be.” This is one reading. Another reading would be to see a tissue of emotion linking “This room, these windows” with the sadness of being one person or having only one life. Seen within a funneled, constraining, ‘small self’ lens, our blank-slate surroundings suddenly become prison walls. They are mirrors: signs validating and reinforcing our depressing mood. The phrase “this frame” is a nudge to see our world as a frame of view only, a peculiar perspective only. Through this frame, which can shift or change at any time, we can easily become “sad at the thought” of our unlived lives, our limited potential. Again, it’s the thought that’s sad. We are talking only about thoughts: points of perspective within frames.

But by discussing the “miraculous” nature of being “called” into someone else’s little life, suddenly “This ceiling, this frame/ this room, these windows” take on another quality altogether, don’t they? They might be humble, marred, sources of unhappiness — hints at missed opportunities, existing elsewhere in permanent grass-is-always-greener springs. But they are now also mildly heroic. They are the result of conscious choices, commitments and sacrifices. They are imprinted with our voices and bodies and Wednesday mornings, our suns and moons, and I am assuming as much laughter as tears and pain. They are the only “frames” we get to have, and we have chosen to share them with, to be “called into” them by, another person, if we are lucky. They are not stop-gaps, annoying bumps along the road to happiness. They are our ‘now’: the content of our lives and our only moments.

No wonder now about the vagueness, the ambiguity, of the stranger or train or walls or ceilings, child or wife or father: who are they to you? Where are you right now? What is your one and only moment, passing away, and how are you holding your mind in response?

If only we could seize this knowledge! If only it wasn’t a small second, felt “Passing in the Hallway”! To extend it, make it permanent, and live with a gratitude we suspect, in those quiet and short-lived moments, we owe to life and others, and we are certain that would make life more worthwhile, more worth the pain it causes, and not revert back to our little prison cells where everything offends and nothing delights.

Post-script quibbles!

The speaker talks about the ‘self,’ but how does one “know self”? Along with other lines of thinking, Buddhism teaches us there is no single thing that can be found or brought forth as ‘self.’ Self is a composite of interdependent forms, feelings, thoughts, choices, consciousnesses; colours, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, thoughts. Self is whatever object is held in the mind or given attention. A cohesive, independent ‘self’ is perhaps the most powerful human delusion and often the root of all our troubles, both gross and subtle. So if we’re reading quickly we might accept, “If love is to know self. If self/ is to know other,” but if we give it our attention and inquiry the line breaks apart into meaninglessness.

So what can we more certainly “know” about another person? Perhaps no other quality that they possess aside from the certainty and the depth of their suffering. We come to, relate to, know others through our pain. Joys are multivariate, but everyone hurts.

If I can be bold, and based on this, these lines might be improved with a small re-arrangement, or another way of phrasing the explanation, which in my mind is less sentimental and more correct: “If love is to lose self. If self/ is to be other.” What do you think?

I usually refrain from commenting on anything someone says about my work, but since you said “What do you think?” I will grudgingly admit that your bold improvement is indeed a fine improvement! It much better captures what I was wanting to say! Good lord.

Anyway, I have lots of thoughts about the rest, but yes, will hold back – will say that you really got to the heart of the poem, and I you’re totally right about my use of vagueness, etc.

Thank you again for your sustained and deep attention.

warmly,

R

Thanks for dropping in, Raoul! You wrote an understated, thought-provoking, and moving poem, and it was a joy to discuss piece by piece. Thanks for humouring my suggestion, too! Ha. Looking forward to your next work, big time.

Love the poems you’ve explored this week. As a new poet, access to this type of deep analysis and critique is extremely useful. Really enjoying this series so far!

That’s amazing to hear! Thank you for reading and for posting a response. I’m really happy this was useful for you. And good luck with your work!